ATLANTA — Fulton County District Attorney Fani T. Willis alleged last month that the Dec. 14, 2020, gathering in Atlanta of 16 presidential electors to cast what they called “contingent” votes for Donald Trump despite Joe Biden’s apparent victory in the state was part of a vast conspiracy to unlawfully overturn the 2020 election result.

Lawyers for three of those electors who were charged in a sweeping indictment along with Trump and 15 others made their first appearance in court Wednesday with a very different argument: that the electors were acting as federal officers, empowered by the U.S. Constitution and federal law — and therefore immune from state-level prosecution. At the very least, the lawyers argued, the three are entitled to prosecution in federal, not state, court.

“By federal law, these people were not ‘fake,’ ‘sham,’ or ‘impersonating’ electors,” Craig Gillen, one of the lawyers, argued Wednesday before U.S. District Judge Steve C. Jones. “They were contingent electors when they did their duty on Dec. 14, 2020.”

The indictment alleges that Trump and his co-defendants conspired to steal the 2020 election through a pressure campaign that included cajoling state officials, harassing local election workers and urging Trump electors to cast ballots in seven states that Biden won. Ultimately, the indictment alleges, the actions were aimed at persuading Congress and Vice President Mike Pence to accept Trump electors’ votes and not those of Biden electors during the final certification of the electoral college results on Jan. 6, 2021.

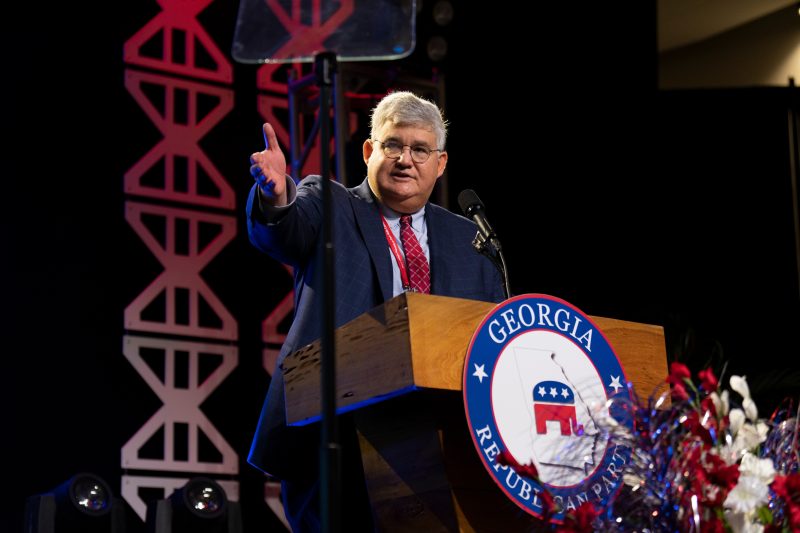

Only three of the 16 Trump electors in Georgia were charged. They are David Shafer, the former chairman of the state GOP; Shawn Still, the former state GOP finance chairman who is now a state senator; and Cathy Latham, a member of the state GOP central committee.

A key element of their defense Wednesday was that federal law — as well as the Constitution — expressly allows states to send more than one slate of electors in the event of a contested election. When they convened, voted and signed electoral certificates that were then sent to Washington, they were acting within the law to preserve Trump’s legal remedies while a lawsuit contesting the Georgia election made its way through court, their lawyers said.

The 41-count indictment includes eight charges against Shafer, seven against Still and 11 against Latham, though only five relate to her role as a Trump elector. (Latham was also charged for her alleged role helping pro-Trump associates illegally access election equipment in rural Coffee County, Ga.)

Charges against the three stemming from their actions as electors include: impersonating a public officer, forgery, false statements and writings, and attempting to file false documents. All three are also charged, as is every other defendant, with violating Georgia’s anti-racketeering statute.

The case is unfolding in Fulton County Superior Court and is the second criminal indictment involving Trump’s attempts to reverse his 2020 defeat. The first prosecution, led by special counsel Jack Smith, was filed in federal court in D.C. in August.

Wednesday’s hearing was in federal court, however, where Shafer, Still and Latham are seeking to move their cases, claiming that they were acting as federal officers. The defendants are pushing for removal under a federal law that allows people charged with crimes while carrying out their official duties to be prosecuted in federal court, even in cases involving state law and state prosecutors.

Two others have also sought federal removal: former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows and former Justice Department lawyer Jeffrey Clark. One of Trump’s lawyers has said he is considering doing the same.

Jones denied Meadows’s request earlier this month, and Meadows has filed an appeal. Clark’s lawyers appeared in court to make their case on Monday, where they argued before a skeptical Jones that their client was acting under the instruction of Trump as president.

Among the reasons the electors might want their case tried in federal rather than state court are potential access to a slightly more Trump-friendly jury pool and a potentially quicker path to dismissal on the grounds that they are immune from prosecution as federal officers.

Although Meadows testified for nearly four hours at his removal hearing, the three electors — like Clark — waived their right to appear in person.

Wednesday’s subject matter was more complicated and nuanced than at either of the previous two removal hearings, and Jones complimented both teams for presenting “excellent” arguments. But the hearing was more sparsely attended than the prior two, and Gillen jokingly complained about it to the judge.

“Now we have to ask people on the street if they want to come in,” said Gillen, a lawyer for Shafer.

The defense team also attempted to portray the three electors as regular people just doing their civic duty by casting their electoral votes.

“This case is not about Donald Trump,” Gillen said. “It’s about three citizens of Georgia.”

Shafer is a businessman who served as state GOP chair “for the grand salary of nothing,” Gillen said. Latham is a retired schoolteacher. And Still, now a state senator, runs a pool-construction company and is facing felony charges for “26 minutes of his life,” his lawyer, Thomas Bever, told the judge.

“He was invited to come to a meeting,” Bever said. “He attended a meeting. He signed a document, and he left.”

Still was the vice chairman of the meeting and was in charge of admitting people into the room. Bever appeared to choke up as he described what he believes is the injustice of the prosecution.

The defense lawyers also mocked prosecutors for characterizing the elector meeting as a secret scheme, claiming the meeting was open and the vote occurred in front of television cameras and in the presence of a court reporter who transcribed the proceedings.

Prosecutor Anna Cross countered that the meeting was not initially open and that the electors welcomed the public and media only after “they were caught.”

Prosecutors spoke for little more than 30 minutes during the three-hour hearing, making the argument for an open-and-shut decision.

“They were not federal officials at all,” said Cross, noting that the legal counsel the electors received came from the Trump campaign, not the Justice Department or White House.

“They were fake electors,” she added. “They were impostor electors.”

Jones interrupted Cross at that point, joking: “Be careful calling them fake electors. You’ve got some people behind you looking you really hard,” alluding to the defense attorneys’ earlier complaints about people calling their clients “fake” electors.

No witnesses testified at Wednesday’s hearing. Instead, lawyers for the electors explained in painstaking detail their view that the U.S. Constitution and the federal Electoral Count Act together protect them from prosecution for their actions — and make clear they were operating as federal officers at the time they met, the threshold for removing the case to federal court.

The Constitution lays out the process by which electors in each of the states, with Congress as the ultimate certifier, determine the outcome of presidential contests. The act fills in the details, setting deadlines for states to certify their results and for electors to meet.

The electors met on Dec. 14, 2020, their lawyers said, because a lawsuit filed by Trump and Shafer was still pending in Fulton County Superior Court. Had they not convened and voted, that legal contest would have been “effectively mooted,” Shafer tweeted at the time.

A key part of the act, the lawyers argued, is its “safe harbor” deadline. In 2020, electors were required to meet on Dec. 14. The safe harbor deadline, which came six days earlier, is the day by which a state must certify its results — with no disputes outstanding — in order for Congress to deem the results conclusive.

In the event a dispute is outstanding — as it was in Georgia — the act provides for electors of both candidates to send their votes to Congress, which then becomes the ultimate decider of the outcome. (If the two houses of Congress disagree, then the candidate certified as winner by the governor prevails.)

“They are equally contingent as a matter of federal law,” said Holly Pierson, another lawyer for Shafer.

And there is precedent for this scenario, the lawyers explained: In the 1960 presidential election in Hawaii, Republican Richard M. Nixon — at the time the vice president, and therefore the president of the U.S. Senate — was certified as the winner of the contest. But state Democrats filed a lawsuit after evidence of counting errors emerged. Electors for John F. Kennedy met and sent their votes to Congress. After the state corrected the count and recertified the result for Kennedy, Nixon declared during the joint session of Congress that Hawaii’s electoral votes should go to Kennedy.

Several tense moments interspersed an otherwise dry hearing. Gillen became animated after he suggested for the second time that this was a politically motivated prosecution of allies of Trump.

“You’re either for Trump or against Trump, and if you are for Trump in any capacity, buckle up, you’re in the danger zone,” he said. “That’s how it goes with this crowd.”

The remark drew a strong response from Cross, who said she was offended at the idea and assured the court that no politics were involved in the prosecution, and if the electors had been Democrats or Libertarians, “they would be standing in the Fulton County courthouse.”