One of the first questions posed to the long-shot challenger for his party’s nomination was a pointed one: Did he view the president as legitimate?

“I think that the election clearly lacked legitimacy,” the candidate responded. “I think the fact that we went ahead and allowed things to proceed is something that has scarred the image of this country. And I think that is why we need to have voting in unprecedented numbers next year.”

This was not a question posed to a Republican candidate in 2023. It was one posed to a Democratic candidate, the Rev. Al Sharpton, 20 years earlier. The presidential election at issue was the one that brought Texas Gov. George W. Bush to the White House — thanks to a narrow victory in Florida that Sharpton and many other Democrats viewed as unfairly determined by the Supreme Court.

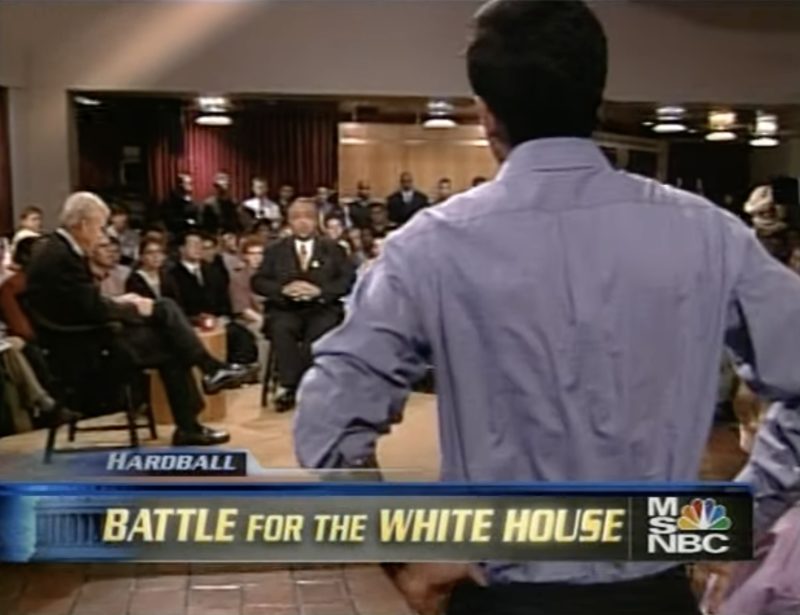

This Oct. 27, 2003, exchange between Sharpton and Chris Matthews, host of the MSNBC show “Hardball,” has reentered circulation in the past few days because there was a 2024 Republican presidential candidate in the room. The event was hosted by the Harvard University Institute of Politics, and Vivek Ramaswamy was a Harvard student at the time. So when Matthews turned to the audience for questions soon after the event started, Ramaswamy was the first to offer one.

“Reverend Sharpton, hello, I’m Vivek,” he began. “I want to ask you — last week on the show we had Senator [John] Kerry, and the week before we had Senator [John] Edwards, and my question for you is: Of all the Democratic candidates out there, why should I vote for the one with the least political experience?”

And right there, you can probably see why the clip has gained new attention. Ramaswamy entered the 2024 presidential race without any experience in elected office, something that was leveled against the candidate during the first primary debate held last week in Wisconsin.

Sharpton, being Sharpton, had a clever response ready.

“Well, you shouldn’t,” he told Ramaswamy, “because I have the most political experience.”

The crowd laughed.

“I got involved in the political movement when I was 12 years old,” Sharpton continued. “And I’ve been involved in social policy for the last 30 years. So don’t confuse people [having] a job with political experience.” Just because an official there in Cambridge, Mass., has a position, he added, “doesn’t mean that they have political experience, and it doesn’t mean they have experience to run the United States government.”

“I think that we confuse titleholders with political experience as we have seen with the present occupant in the White House,” Sharpton continued. “George Bush was a governor and clearly has shown he doesn’t have political experience.”

Ramaswamy, of course, would substitute his business background for Sharpton’s experience in social activism. But Sharpton was also almost 50 years old in 2003, 12 years older than Ramaswamy is now.

The current candidate’s critics note not only that his question suggested that those without experience in elected office should be viewed with skepticism but that he was considering voting for a Democrat in the 2004 primary — itself an obvious point of criticism for his opponents. There’s a trivial rejoinder Ramaswamy can offer, of course: The most recent Republican president was a guy with no political experience who used to vote Democratic.

The emergence of this video snippet marks a broader evolution than Ramaswamy’s own, of course. As years pass, it will become only more common for candidates to be presented with their past comments or views, thanks to the increase in how often we are recorded and how easy it is to retrieve those recordings. Even when we aren’t recording ourselves, we’re often around cameras. And the ability of automated systems to pick out our faces from even blurry, crowded photos and videos continues to improve. A 37-year-old candidate running for the presidency in 2044 will have grown up entirely in the iPhone era. Good luck to her, escaping her past comments.

In its totality, the exchange between Matthews and Sharpton is a remarkable political time capsule. It occurred only weeks after Arnold Schwarzenegger usurped California Gov. Gray Davis’s position in a recall election, something that Sharpton lumped in with the 2000 presidential results to declare that “we’ve gone through a nonmilitary civil war.”

That was one of Sharpton’s approaches to the nomination that year: Pick up rhetoric from the activist base of the party and hope to parlay it into votes. It’s what Ramaswamy is doing this year, albeit with a more virulent base and a flimsier anchor to established political values.

Sharpton made it to mid-March 2004, earning no delegates. Kerry, who spoke at Harvard the week before Sharpton, got the nomination. In November, Bush was legitimately elected to a second term in office.

Not exactly the path Ramaswamy or his party want to follow.