It’s no secret that the House has had a tough two years.

One speaker, Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), got ousted mid-term, and his successor, Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.), survived a coup attempt only because Democrats spared him. The most basic procedural votes have become herculean tasks. Legislative output has cratered.

Now, with Election Day nearing and the Democrats within a few seats of the majority, some see a chance to try to fix what’s broken by taking up a reform push they started after winning the majority six years ago — but clearly never finished.

Moments when power changes hand offer the best chance at reshaping how Congress acts, and that is doubly so when a new leader takes charge.

In 2018 a small group of moderate Democrats used the opportunity to create a temporary House committee tasked with modernizing the chamber. The committee lasted four years, received plaudits for some important-but-modest changes and has since had its work folded into a subcommittee.

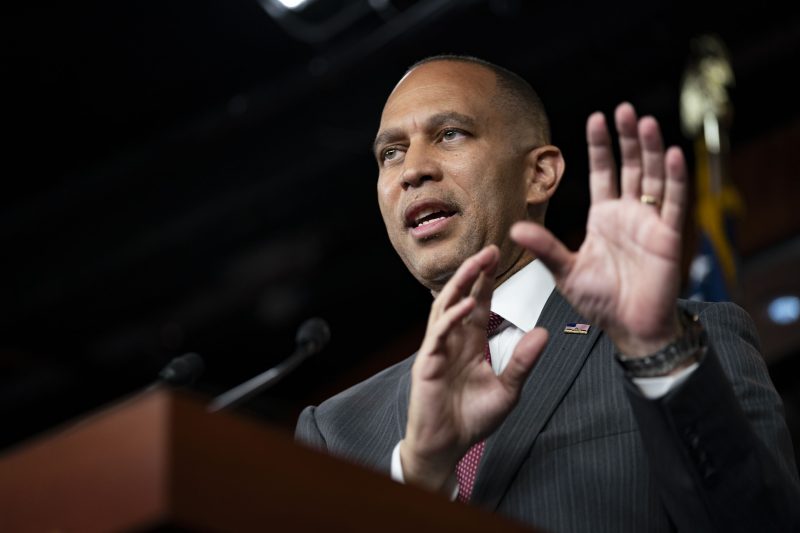

But for House Democrats, Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) as speaker could mark a sea change, especially compared with six years ago, when Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) returned to power.

Pelosi had already served four years as speaker (2007-2010) and had been leading Democrats for 16 years, with a very experienced leadership team that was more bound by tradition. Just 12 years into office, Jeffries, 54, could be more open to trying out new ideas, according to several former aides and retiring lawmakers.

Jeffries would have his work cut out for him. Even Democrats acknowledge that, in their previous four years of holding the majority, the institution wasn’t exactly performing up to par. Rank-and-file lawmakers have an endless list of complaints, from scheduling conflicts, to committee chairs disregarding junior members, to leadership ignoring the work of those legislative committees.

“While tremendous progress has been made, there is still much more work to be done,” a group of 10 think tanks and congressional experts, dubbing themselves the “Fix Congress Cohort,” wrote in a recent letter to congressional leadership.

There is no shortage of proposals. The Washington Post’s editorial board this week highlighted a working group of former members of Congress, run through the University of Pennsylvania, that is circulating ideas about how to change the cultural norms.

“Partisan conflict explains a lot of the Hill’s dysfunction, but so do relatively fixable internal rules, written and unwritten,” The Post’s editorial board wrote.

Just as some of the most interesting ideas for overhauling the Senate came from former senior GOP staff, a similar survey of former House Democratic aides offered up some interesting and surprising ideas.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity to avoid any blowback from current or former employers, these ex-aides generally diagnose the same problem: The average lawmaker feels removed from the process, and even when they can come up with bipartisan ideas that have support, their bills languish.

These half-dozen former aides served in high leadership posts, ran legislative committees or worked as chief of staff for rank-and-file Democrats, each with more than a decade of experience. Their ideas covered many aspects of how lawmakers exist, from what committees they serve on to how much they travel and to how often they are fed during meetings.

One former aide noted the dilemma of many junior lawmakers receiving two and sometimes three committee assignments. This can lead to lawmakers having legislative hearings at the same time, forcing them to either skip one or race around the office buildings trying to attend part of each hearing. And because so many lawmakers receive so many assignments, these committees are larger than ever and hearings take too long because every member is allowed to ask at least five minutes of questions.

If lawmakers received fewer committee assignments, their daily lives would be easier to manage and they could drill down on fewer issues to develop real expertise, according to the former aide, who served as chief of staff to two rank-and-file Democrats.

In addition to an avalanche of committee work, lawmakers have created an endless list of “congressional member organizations,” groups that serve as caucuses supportive of issues and causes.

These are well meaning but also serve as passing attempts at checking political boxes rather than actual policymaking. Rep. Greg Landsman (D-Ohio), a freshman, serves on 21 of these caucuses, while another freshman, Rep. Michael Lawler (R-N.Y.), serves on almost 60.

Two former Democratic chiefs of staff suggested tightening the reins on these ad hoc groups — ranging from the Wine Caucus to the left-flank Progressive Caucus — by cutting back on their funding, as they eat away a member’s time and also sometimes drive ideological division within internal party ranks.

Another common complaint is how hard it is for legislation, despite bipartisan support, to get to the full House for a vote.

Data shows the shrinking ambition in the House. Back in 2016 — the last year when Republicans ran the House against a Democratic president — the chamber approved 659 bills and resolutions. Through the first eight months of 2024, the House had approved just 353 measures.

Centrist Democrats, working with moderate Republicans, tried to create a fast-track calendar six years ago for bills with wide support, but that practice faded away quickly and instead the legislative calendar is dominated by the speaker and his leadership team.

The “suspension calendar,” as the current process is known for passing noncontroversial bills quickly with a two-thirds majority, needs to be updated so that more bills with broad support can get to the floor for full votes. Most rank-and-file lawmakers like to tout that their chamber approved one of their bills and, if it does not make it into law, they will try again next year to win Senate approval and a presidential signature.

Another idea to make legislative committees work together was a formal requirement that each panel’s full membership attend either a retreat outside of Washington or an official trip abroad to study an issue together.

These congressional delegation trips are known for creating lasting bonds among lawmakers, while also opening their eyes to how policy made in Washington impacts the real world.

Some former aides believe it’s time to come up with a better acknowledgment of remote work. At the height of the pandemic, the proxy voting system seemed appropriate to allow social distancing and prevent members from traveling and potentially spreading the coronavirus.

Lawmakers were supposed to certify they were unable to travel to Washington out of fear of attracting or spreading the virus, allowing a member in the Capitol to cast their vote for them. Over time it turned into an excuse to skip work, as some Republicans once trekked to the southwest border with ex-president Donald Trump and some Democrats flew on Air Force One with President Joe Biden to Michigan.

Republicans eliminated the practice altogether after winning the majority in 2022, but as one former Democratic aide argued, the current policy can be unnecessarily harsh. A woman who cannot travel because of pregnancy complications should be allowed to cast her vote, the former aide said. A bipartisan pair of House members have proposed proxy voting for up to six weeks after giving birth.

Just as some ex-GOP staff in the Senate want to curtail political showboating, one former House Democratic aide suggested that once a month, or every few months, one bill should come to the floor in a debate that would not be televised.

The visiting public and press would still be in the chamber to monitor the legislative debate and votes, but the TV cameras would be off to make lawmakers simply debate among themselves.

Finally, another former aide had a striking idea: Eliminate food at most meetings inside the Capitol complex. Food and beverage are standard at many meetings. A large portion of it goes to waste and, the aide argued, offering the food tends to make meetings go longer than necessary.

Most lawmakers and aides agree that Congress needs a more comprehensive overhaul than some of these modest proposals, but some small steps would help.

As the “Fix Congress” group noted in its memo, “Gradual progress is more likely than sudden and comprehensive approaches.”