SANTA CLARA, Calif. – Class is in session.

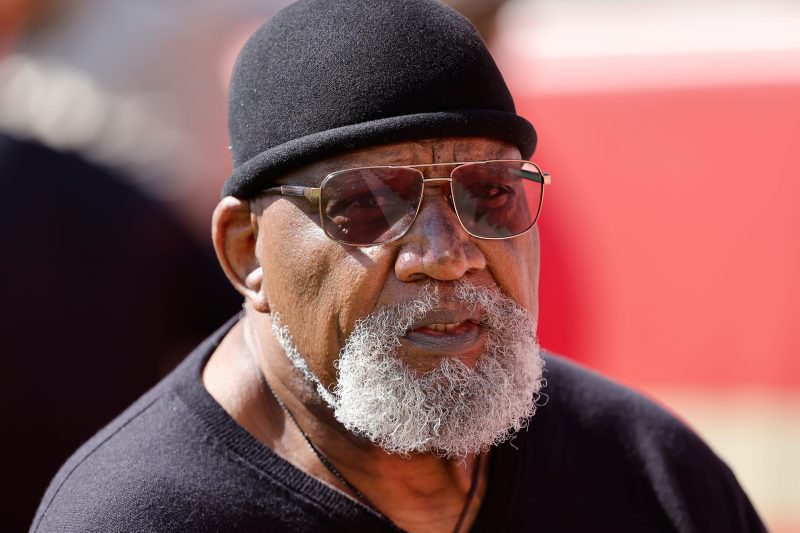

As usual, a lesson from the esteemed Harry Edwards positions us at the intersection of sports and society. It comes with historical context, underscoring the significance of one Black athlete after another. It amplifies, with powerful eloquence that is quintessential Edwards, struggles and evolution of the civil rights movement. And the renowned activist doesn’t hesitate to tell you that it is hardly finished business.

Typically, Edwards, a longtime consultant for the San Francisco 49ers and once the most popular professor at Cal-Berkeley, uses personal experiences to illuminate messages. During the late 1960s, while earning his Ph.D. from Cornell, he organized the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which produced the raised-fist protest by Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the medal stand during the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

He rolled with the Black Panthers and was under surveillance by the FBI, with J. Edgar Hoover personally overseeing his case. He can drop so many names, and so casually, of people he has more than merely encountered on his journey: Maya Angelou. Martin Luther King. Jim Brown. Bill Walsh. Bill Russell. Colin Kaepernick.

There are so many places that Edwards can take us on a continuum of enlightenment.

SUPER BOWL CENTRAL: Latest Super Bowl 58 news, stats, odds, matchups and more.

Yet as Edwards, 81, reflected for more than two hours at 49ers headquarters earlier this season, this particular lesson included a theme for which he is not famous: life and death.

‘Stuck a screwdriver in a bone and started twisting’

Edwards was diagnosed during the spring of 2022 with myeloma, a cancer that develops in the bone marrow and threatens to spread throughout the body. Without a cure and determined to reject various forms of treatment, he has battled excruciating pain for months.

‘If you sit here and watch me get up out of this chair, you’ll wonder why I even bother,’ Edwards told USA TODAY Sports. ‘I’m almost living on quick-release, maximum-strength Tylenol every two, three hours. Pain in my bones, clavicles, hips, spine, my back.

‘It’s far enough down the road where I know I have to be careful getting up, because sometimes I go to stand up and one side, or both sides, from my hips down, just disappear like they evaporated, like I’m falling. And that’s a big problem with this condition.

‘So it’s something that I’m aware of, and I just have to roll with it. To manage it, I’m sometimes eating Tylenol like it’s popcorn. But that’s what it takes, and it doesn’t dull my faculties. I’ve talked to a number of doctors; there’s stuff that I could take to ameliorate the pain, treatments that might slow the pace … but there are side effects. There is no cure.

‘But one thing after the pace is slowed and it’s even halted, when it comes back, it comes back with a vengeance. So there’s that dimension. The pain is really bad news. I don’t know if it’s the 80 years or the myeloma. But it feels like somebody stuck a screwdriver in a bone and started twisting.’

At first glance, Edwards looks as imposing as he was during the early 1990s, when I met him while working for The Marin (County) Independent-Journal as a 49ers beat writer. He’s a well-built 6 feet, 8 inches (which is one reason why two NFL teams and an NBA team in the early 1960s dangled tryout options, which he shunned to pursue a career in academics), and despite his illness, has kept his weight on. The thought of cancer weakening his body is not easy to decipher. He has always seemed so powerful, with a booming voice and incisive wit that matched his physique.

In mid-January, Edwards received good news after undergoing another battery of tests. Doctors told him there has been no increase in myeloma markers since his previous round of extensive tests in May. He realizes the disease is unpredictable, that it is possible he can remain stable for 10 years … or suffer a setback that rapidly progresses.

As of late Thursday, Edwards wasn’t sure whether he would attend Super Bowl 58. He said doctors have ruled out air travel due to the potential for developing blood clots, leaving the possibility of driving to Las Vegas. He is content with the notion of watching on the 105-inch screen at his East Bay home, yet will leave the final decision to his wife of 54 years, Sandra Boze.

Standing on the sideline Sunday during pregame warmups for the NFC title game at Levi’s Stadium, he said Boze was moved as she stood with him during an on-the-field tribute from the 49ers before the NFC divisional playoff game. The 49ers honored Edwards for his lifelong commitment to social justice and education. It would not surprise Edwards if Boze wants to be on hand at Allegiant Stadium.

Regardless, he insists he will not stress over his condition.

‘You know what? Like I’ve said before, I did not expect to live to be 30,’ said Edwards, who grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois. ‘People were dying all around me. I think about 39 years old, Malcolm X. Dr. King, 39. Some of the young people who were in the movement with me, and the Black Panther Party, 20, 21. Fred Hampton was 21. When I was out there, I was 24.

‘To live to be 81 years old, man, what do I have to be whining about?’

No, it is Edwards’ style at whatever age to carry on with purpose. Despite this adversity, that spirit hasn’t waned.

‘What I look at is how much can I get done with whatever amount of time I have left,’ Edwards said. ‘To do some things that will amount to a contribution. And the rest of it, you know what? I look at it like my (three) children, my two grandsons, my former students, athletes here that I know and have talked to – like K.T. (Keena Turner), Ronnie (Lott), Joe (Montana), Roger Craig – all of these people are also watching.

‘They need to know that even this stage of life can be handled with dignity, grace and even a sense of humor.’

He mentions that when he decided to pursue a career in academia, he signed up for life. And that includes now.

‘I can still be teaching on my deathbed,’ Edwards said. ‘And if that’s the case, I’ve made a contribution. Even in this context.’

It’s about contribution, not legacy

It was striking to hear this icon of social activism express desire to make more contributions. Is he kidding? Throughout his life, Edwards has been such a major-impact player, so to speak. He created an entirely new academic discipline linking sports and society. Over several decades, he has been the preeminent voice for the plight of Black athletes. Yet this is arguably Edwards’ great gift continuing to operate.

In recent months, Edwards completed two important projects he feels will make lasting contributions: a 12-part video series, ‘The Last Lectures,’ that covers the history of activism over a span of more than 150 years; and a six-part documentary, ‘The Struggle and the Power,’ with a similar theme intersecting sports, race and activism. While talks for the distribution of the projects are ongoing, Edwards is also aiming to complete a documentary on Joe Frazier and has narrated a three-hour oral history on sports activism.

‘At some point, I’m going to sit down,’ he said.

Why has he been so busy? Is Edwards driven to cement his legacy?

‘Legacy is something that somebody else is going to write,’ he fires back. ‘Because I won’t be here. I don’t concern myself with things that I’m never going to be able to experience. What I’m interested in, in terms of these pieces, is not legacy. I’m interested in contribution. I want to make sure that people will look back on these films, along with a scholar-athlete life, and say, ‘I learned something.’

‘Somebody asked me how I would assess the contributions of Jim Brown, Bill Russell, Elgin Baylor and Arthur Ashe. I said I always ask one question, and one question only: Did they make a contribution? That’s the key question. Not legacy.

‘Legacies can be phony-ed up. Legacies can depend on who’s writing the book. Contributions depend on what you actually do. Not what somebody said about you. What did you actually do? So that’s where I come down on that.’

This reminds Edwards of something that fellow activist H. Rap Brown told him that he has found to be true. Brown said only the people and the struggle survive.

‘Individuals never survive and very, very few are truly ever remembered,’ Edwards said. ‘We have a tendency, and social media has made it even worse, to reduce people to characters. To reduce them to sound bites.

‘I mean, Malcolm X is, ‘By any means necessary.’ Dr. King is, ‘I have a dream.’ Rap Brown is, ‘Burn, baby, burn.’ Stokely Carmichael is, ‘Black Power.’ But when you ask what contributions they made, you have to go much deeper.’

Lifelong educator also taught life lessons

Edwards has been reminded in recent months of some of his contributions, as word about his condition spread. He’s heard from hundreds of his former students at Cal-Berkeley and San Jose State, expressing appreciation for the impact he’s had on their lives.

‘That’s what a teacher really lives for,’ he said. ‘For a student to say, ‘You made a difference. You changed the way I looked at the world.’ That’s what really matters to me.’

Having picked Edwards’ brain dozens of times over the years, for formal interviews, background perspective or just during general conversation, I can imagine what it would have been like to have been one of his college students, exploring sports and society. That would have been lit, as the kids say today. When I told him that, he laughed.

‘Don’t feel bad about not going to Cal and taking my class,’ he said. ‘You probably wouldn’t have been able to get into my class. They would have an enrollment for 550 and 1,100 people would show up. And they would stick around, even after the deadline for enrolling, hoping that somebody would drop the class, that they’d be able to just go and get a seat one day.’

Edwards recalled being told by a fellow sociology professor there was a problem. Edwards would attract roughly 700 students for his classes, while other classes in the same window would have fewer than 20 students, he explained.

‘They tried moving my class to lunchtime,’ he remembered. ‘Didn’t make a difference. They tried 4-5 p.m., dinner time. Same thing. There would be 600 to 700 students in my class.’

When Walsh brought Edwards to the 49ers in 1985, a large part of the purpose was to teach players life lessons. ‘What I had to say, Bill realized that he didn’t have the time nor capacity to teach,’ Edwards said.

It was a different setting in one sense — Walsh told him his office was ‘the building’ and ‘the locker room’ — yet completely familiar territory for a man who to this day is the only captain of two teams (basketball, track and field) at San Jose State. He connects.

I saw it during the early ’90s, when the talented team included the likes of Jerry Rice, Tom Rathman, Harris Barton and Jesse Sapolu. And I saw it recently, too, walking with Edwards at the 49ers compound after players had just bolted from a meeting. George Kittle waved and spoke. Deebo Samuel stopped, served up a bro-hug and engaged in quick chit-chat with Edwards. The respect was palpable.

Keena Turner, who played his entire 11-year NFL career as a 49ers linebacker from 1980-90, is Edwards’ point man with the 49ers these days. A vice president and senior adviser to GM John Lynch, Turner has been in the team’s front office for 27 years.

‘He can go anywhere he wants to in the building,’ Turner told USA TODAY Sports. ‘We just want to know he’s here.’

During an exchange with Turner in the parking lot, Edwards couldn’t contain his excitement about Brock Purdy, the young quarterback who has emerged since being the last player drafted in 2022. Edwards is so impressed that he maintains Purdy could become one of the greatest 49ers ever — which is a mouthful when considering legends including Montana, Lott, Rice and Steve Young.

Turner stopped him.

‘That’s a statement to be made in hindsight,’ Turner told Edwards. ‘You taught me that.’

With that, Edwards let out a hearty bellow.

‘Harry, don’t get my daughter killed’

There is no shortage of compelling reflections from Edwards. Why did he come to California in the first place? Edwards wanted to play football at USC.

‘I had read about this college coach at USC who had named a Jewish kid, Ron Mix, and a Black kid, Willie Wood, co-captains of the team,’ Edwards said. ‘He got much blowback. Threats. His response was to name them co-captains again the next year. So I said, that’s where I wanted to go.’

The coach was Al Davis, who coordinated the Trojans’ offense from 1957-59. USC arranged for Edwards to begin with a year at a feeder school, Fresno City College. After one semester (and with a national junior college record in the discus), he transferred to San Jose State – which is where his academic career took off.

When Edwards wound up at Cornell as a prestigious Woodrow Wilson fellow, he was told that on average, it took 8 1/2 years to earn a doctorate degree. He proceeded to finish his classwork in two years, took two years off as he delved into the Olympic protest project, then wrote a 1,105-page dissertation he said is the longest in Cornell history. That morphed into an integrated textbook, ‘The Sociology of Sport.’ He earned his Ph.D. in five years.

‘They thought I was a big, dumb ex-jock looking for an easy way out,’ he said.

Another vivid memory was the day he met Boze’s family during the latter half of the 1960s in Los Angeles. By then, as the 1968 Olympics approached, Edwards had a very high profile as an activist.

‘She came home with a big Afro, big earrings, and her folks said, ‘Wait a minute,’ ‘ Edwards recalled.

Boze introduced Edwards and revealed their plans to marry. She wanted her parents’ blessing.

Her father flatly told Edwards: ‘Harry, don’t get my daughter killed.’

‘What he was really telling me was, ‘If you get my daughter killed, I’m coming for you,’ ‘ Edwards reflected. ‘And he was a non-violent guy, a schoolteacher.’

‘No sir, I’m not going to do that,’ Edwards replied.

Edwards and Boze have endured for well over a half-century, facing a series of private challenges on top of the public issues Edwards is known for.

‘You know who my real source of courage, vision and insight is for this? My wife,’ Edwards said. ‘Double mastectomy. Melanoma. High blood pressure. And she has never stopped smiling. Never stopped laughing. The same lady for 54 years. And she’s handled it. I wish I had the level of courage that she has.’

Edwards believes that the situations where he supported his wife with her health challenges helped prepare him to manage his current condition. Undoubtedly, that works both ways.

‘She worries too much about me,’ he said. ‘But that’s her make-up. This nurturer who wants to take care of this.’

The key to everything

The 49ers have provided more teaching moments. And reflections. Edwards sees the dynamic between coach Kyle Shanahan and Lynch, and it reminds him of how Walsh interacted with his GM, John McVay. He thinks Walsh would be proud of the culture that is seemingly well-established with the current team.

‘One of the things Bill Walsh said when asked about the greatest characteristic of his best teams was that they cared and respected each other,’ said Edwards, who delivered the eulogy at Walsh’s funeral in 2007.

‘And when I look at this team and I see what Fred Warner thinks about (Nick) Bosa, and what Bosa thinks about Trent Williams, and what Christian McCaffrey thinks about Purdy, and what Purdy thinks about (Brandon) Aiyuk, (Jauan) Jennings and Deebo, and the way they interact and how they embrace each other’s challenges, it reminds me of Joe and Steve, and Jerry and John Taylor. It reminds me of Tom Rathman and Roger Craig …

‘Not because of the winning and productivity, because they didn’t always win. But they were always together on it.’

Edwards sees society at large when he ponders the 49ers, past and present. Society, he insists, can heed lessons that include honoring diversity.

‘This team, there’s a magic to them because they care about each other,’ he said. ‘That is the key to everything. I think sports recapitulates society. The key to dealing with almost every major problem we have in this country – the economy, the divisions between us, the international posture of the United States – it’s going to have to begin with the simple fact that we care about each other on a very human level. And if we don’t do that, we’re doomed.’

And that’s a lesson for the ages.